Being self-sufficient in procedures and depending on only their skills and tools gives all practitioners the confidence that they are in total control

Being self-sufficient in procedures and depending on only their skills and tools gives all practitioners the confidence that they are in total control

In an article back in 2017, I discussed how learning has changed from the days of ‘see one, do one, teach one’, and highlighted how surgical training is effectively a continual series of learning curves that can jeopardise patient safety and leave surgeons open to claims of negligence (Spang, 2017). In this follow-up article, these ideas will be developed through describing how pre-procedure preparation gives both surgeons and non-surgical practitioners self-sufficiency in operations and procedures, so that they only need to depend on themselves and their tools. The confidence that they are in total control can help to guard practitioners against situations that have been commonly seen in the COVID-19 era.

Learning curves

Learning curves rarely end after surgeons and practitioners qualify and, with the introduction of new innovations and procedures, they will continue to persist throughout their careers. This is far more common nowadays than it was even 15 years ago, as technology progresses and ideas are shared more fluidly online between practitioners across the world. Often, new innovations in aesthetics focus on improving the patient's outcome and satisfaction by reducing post-treatment complications, or removing the strain of surgery by streamlining complex techniques. However, the outcome of the procedure, whether non-surgical or surgical, is also correlated with the experience of the surgeon or practitioner, among other factors. So, the newer the innovation, the further along the theoretical learning curve the surgeon or practitioner must go.

Once overcome, learning curves ultimately lead to better surgical and non-surgical prowess that continues throughout a professional's career, improving the safety of their future procedures. However, safer practice is also reliant on adequate preparation and reliable equipment to lighten the strain of procedures. To begin a procedure, surgeons and practitioners must physically and mentally prepare for the task ahead, and how they choose to do this is at their own discretion.

» Being self-sufficient, whether in an operating theatre or an aesthetic clinic, allows both surgeons and non-surgical practitioners to be in total and utter control «

Mental and physical preparation for surgery

Surgery is undoubtedly a complicated and physically demanding procedure for even the most trained surgeons and their patients. With a procedure as life-changing as surgery, practitioners are, of course, going to prepare for it in every way that they can. This includes honing their surgical capabilities with optimal training and experiences, and ensuring that they are equipped with dependable resources. Prior to the procedure, the tasks that they undertake often prepare them for a state of physical and mental readiness—much like a pilot's checklist before flying. Each surgeon will have their own method of preparation, from mentally rehearsing each step to ensuring that they are well-rested, have found the balance between being hydrated and an empty bladder and can harness the energy to focus. It is even thought that simply forming a power stance for 2 minutes prior to surgery can shape the mental mindset of a clinician and increase their confidence levels (Carney et al, 2010).

Once in the operating theatre, equipment, such as loupes and surgical headlights, are adjusted to provide uninterrupted vision, and distractions are minimised so that the surgeon can feel calm, confident and focused on the task ahead. For a novice, having a step-by-step agenda to achieving the ultimate level of preparedness is essential as they become more familiar with surgeries and overcome their learning curves. Reducing traffic in the operating theatre can also be an excellent way to cut the risk of infection, limit distractions and help maintain focus—all of which contribute to improved surgical outcomes.

Many hands make more work

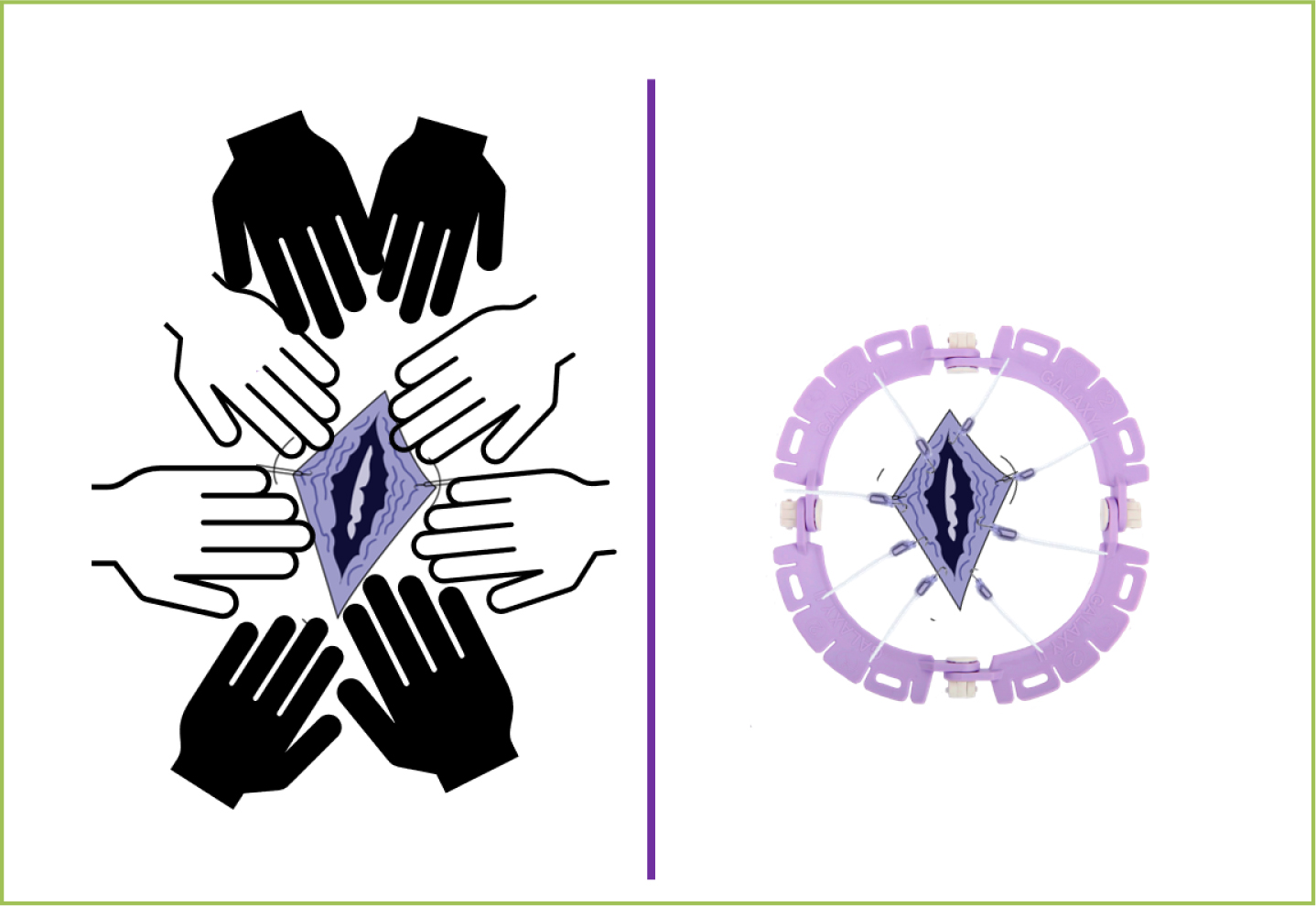

The saying often goes that ‘many hands make light work’, but this is quite the opposite for surgical procedures, where too many hands expose the patient to greater threats of infection and the potential for human error. For even a simple task such as retracting the skin, eight points of contact are ideal for holding the skin back effectively and maintaining a taut retraction (Figure 1). Where this is the case, the help of an assistant—or, more likely, multiple assistants—is undeniably valuable when there is no alternative; however, they require their own training and have their own learning curves to overcome. Precious theatre time for the surgeon can be taken up explaining how and where they need an assistant's help, or worse, their focus may be diverted to intervening or readjusting their work at a pivotal point.

Figure 1. Eight points of contact

Figure 1. Eight points of contact

This is where items such as retractors can significantly help, as they give surgeons a clear view of the surgical site without the distribution of multiple hands, and allows them to dedicate their full attention to the procedure—a certainty that is reassuring for both the patient and surgeon. In all operations, but particularly in the aesthetics field, minimal scarring is pertinent to patient satisfaction. Every successful operation is not only a triumph for that patient, but also an advert for attracting future clients. By avoiding distractions during incisions and sutures, a surgeon is more likely to achieve clean cuts and avoid tearing to accomplish a consistently high record of patient satisfaction. Without this equipment, negotiating a busy surgical field with multiple assistants and distractions proves even more challenging during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Adjusting to a new reality

Preventing post-operative infections has always been the greatest concern for surgeons and patients and, in light of the COVID-19 pandemic, this now carries a deeper meaning. Priorities have shifted since before the pandemic, and minimising the number of people in an operating theatre at one time, to, firstly, reduce infection risk and, secondly, reduce reliance on assistants where staff shortages are likely, has become a significant consideration. Suddenly, what was a routine procedure with minimal preparation could no longer bring the same certainty and ease that it did prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. Through this community-wide learning curve, clinics needed to either implement approaches for both surgeons and non-surgical practitioners to become more self-sufficient or face closure. Being self-sufficient, whether in an operating theatre or an aesthetic clinic, allows both surgeons and non-surgical practitioners to be in total and utter control so that they can focus on the task at hand; they want to be able to rely on their tools—and only their tools—for the safety and efficacy of procedures.

Conclusion

Now, more than ever, it is important that ways to avoid relying on colleagues for the success of procedures are sought out. If you suddenly find yourself with fewer staff members, would you be able to cope? Being self-sufficient in procedures and depending on only themselves and their tools gives all practitioners the confidence that they are in total control.