Nurse prescribing has come a long way since the Cumberledge Report in 1986 (Department of Health, 1986) and continues to be a privilege that nurses and other health professionals work hard to attain. Currently, nurses can undertake an additional programme of study to become independent and supplementary prescribers (IP/SP). These prescribing qualifications are grounded in law, and upon successful completion, the prescribing status is annotated on the Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) register. Having gained my qualification to become an independent prescriber (IP) some years ago, I have decided to take this opportunity alongside the lead of the V300 prescribing course at Northumbria University, Dr Claire Pryor, to reflect upon how non-medical prescribing has evolved, how it applies to aesthetic practice and examine recent changes and how this has impacted my practice.

» Practicing in aesthetics does not set aesthetic nurses aside from any other nurse in terms of professional work and regulation «

History

The evolution of non-medical prescribing spans decades from the Cumberlege Report in 1986, Neighbourhood Nursing: a Focus for Care. This report recommended limited prescribing rights for community nurses with district nurse or health visitor qualifications to save time and provide better care. The Crown Report 1989 endorsed nurse prescribing and highlighted the circumstances in which it could occur, this was followed by primary legislation (1992) which provided the power for nurses to be able to prescribe. (Medicinal Products: Prescription by Nurses Act, 1992). This was followed in 1994 with Commencement No1 of this Act. The second Crown Report (1999) recognised the importance of having other appropriate Health Care professionals be given prescribing rights. In 2002, following the Health and Social Care Act 2001, the prescribing qualification for the extended prescriber (from a limited formulary) was launched. The following year (2003) nurses and midwifes were permitted to take on the role of supplementary prescribers. Building on from this, the majority of the BNF became available to independent nurse prescribers in 2006 (but limited to the individuals' scope of competence and confidence), with further legal changes over the ensuing six years, which allowed the prescribing of unlicensed and controlled drugs (2012), with some exceptions in relation to the treatment of addiction (Joint Formulary Committee, 2023). Over the past two decades, with additional training and education, independent prescribing can now be undertaken by a range of other health care professional such as radiographers, podiatrists, physiotherapists, and advanced paramedics (RPS, 2021). More recently, there has been a drive to increase the number of pharmacist prescribers, cumulating with prescribing now being embedded within pharmacist education, leading to registration (General Pharmaceutical Council, 2023).

Mather and Maw (2017) discussed that prior to 2012, many aesthetic nurse practitioners were administering prescription-only treatments, such as botulinum toxin treatments, following a remote consultation carried out by a doctor from which a prescription would be emailed to the treating practitioner. Although this, at that time, was not seen as problematic by the General Medical Council (GMC), it was viewed as bad practice by the NMC. This manner of practice was not questioned by many aesthetic nurses as it had become commonplace, giving scant regard to the professional accountability demanded by the NMC (2006) and national prescribing legislation (Department of Health, 2006a). This serves as one example of how the lines of safe and ethical practice have become blurred in the transition from the more traditional nurse/doctor roles, into the roles of aesthetic practitioners. As aesthetic practice has evolved, it has brought with it some outstanding and innovate practice from health professionals, but it has also become apparent that some unacceptable behaviours and practice have become, at times, normalised, within the aesthetic sector. This leaves a lot to be considered in terms of the history of medicine and the evolution of nurse prescribing. As aesthetic nurses remain nurses at the core, it is imperative that we abide by the stringent code of practice, and maintain contemporary, evidence-based clinical skills and knowledge. Practicing in aesthetics does not set us aside from any other nurse in terms of professional work and regulation. By striving for and maintaining high standards of practice, the majority of aesthetic nurses are paying homage to how hard they have worked in order to gain their prescribing rights, clinical skills, autonomy, and professional recognition. Considering the advancement of nursing outside of traditional disease process models, we feel that the aesthetic practice offered by regulated health care professionals is a golden egg of opportunity which we have managed to drop at times.

» Aesthetic nurses remain nurses at their core, and they must abide by the stringent code of practice, whilst maintaining contemporary, evidence-based clinical skills and knowledge «

Non medical prescribing

Prescribing activity undertaken by healthcare professionals other than doctors or dentists is termed non-medical prescribing. It is worth noting here that there is often confusion with regards to Health & Care Professions Council registrants and midwifes prescribing within the aesthetic sector. It is important to remember that prescribing rights are aligned to the practitioner's professional registration, and the scope of practice for that profession (i.e. scope of practice for nurse/midwife/paramedic etc). Whilst practice is ever evolving, recent communications from the HCPC and NMC directly to the authors, alongside formal guidance and statements issued by professional colleges such as the Chartered Society of Physiotherapists (2021), Royal College of Podiatry (2023), and Health Education England (2015) indicate that only nurses (in all fields) can prescribe for cosmetic/aesthetic purposes and give clinical oversight to other aesthetic practitioners, and only once they have completed and consolidated their own aesthetic practice knowledge and skills. Any midwives or HCPC professionals who are unsure of their regulator's support and stance regarding their ability to prescribe for aesthetic purposes should contact them directly for guidance.

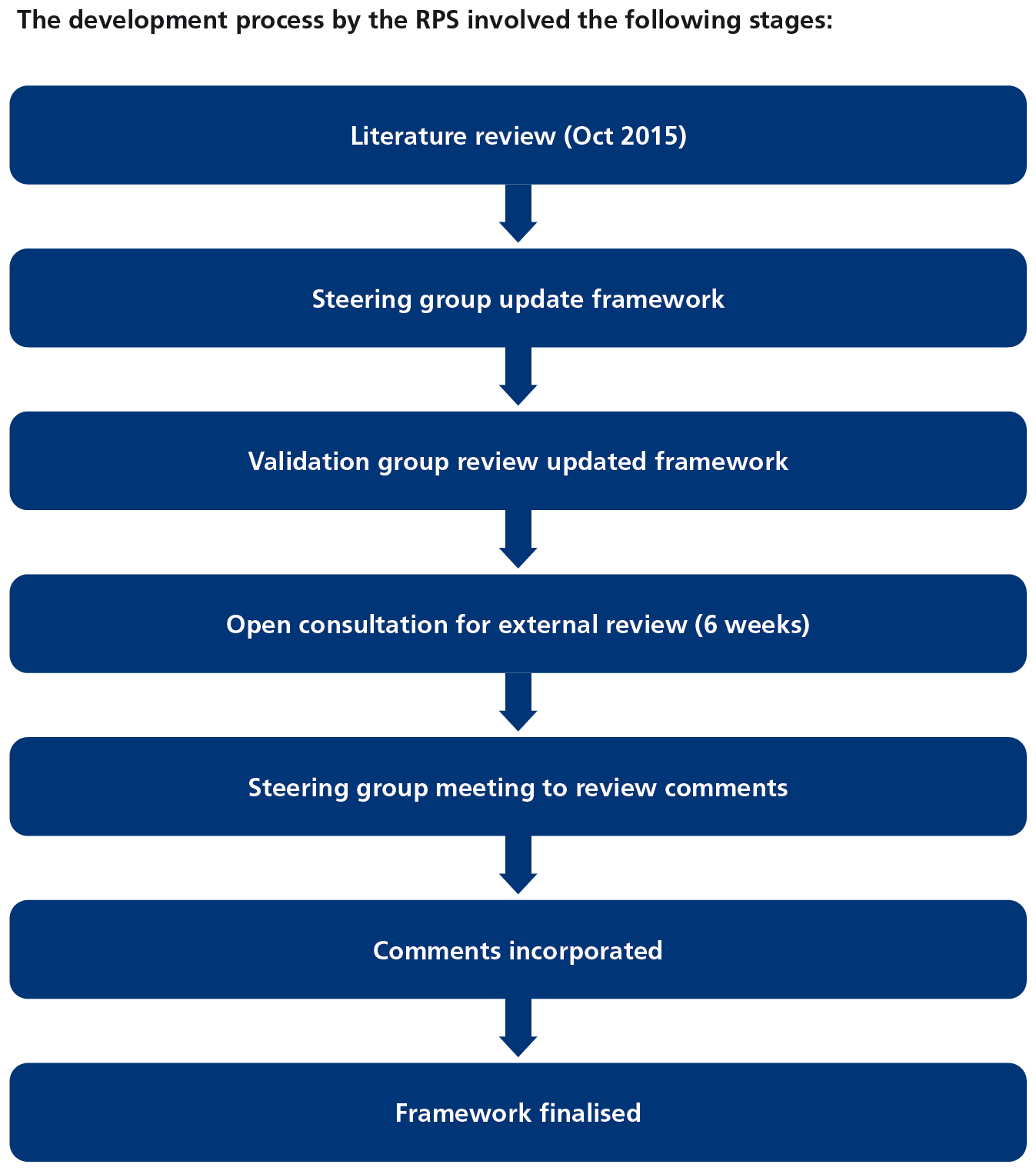

In 2012, in order to support non-medical prescribing, a single prescribing competency framework was published by the National Prescribing Centre. Competency frameworks are seen as essential to achieve higher organisational performance by setting out new organisational requirements. In 2014, NICE and Health Education England (HEE) approached the Royal Pharmaceutical Society (RPS) to manage the updating of the framework. The RPS agreed to carry out this update in collaboration with patients and other prescribing professionals. From this collaboration the RPS (2016) competency framework for all prescribers was developed.

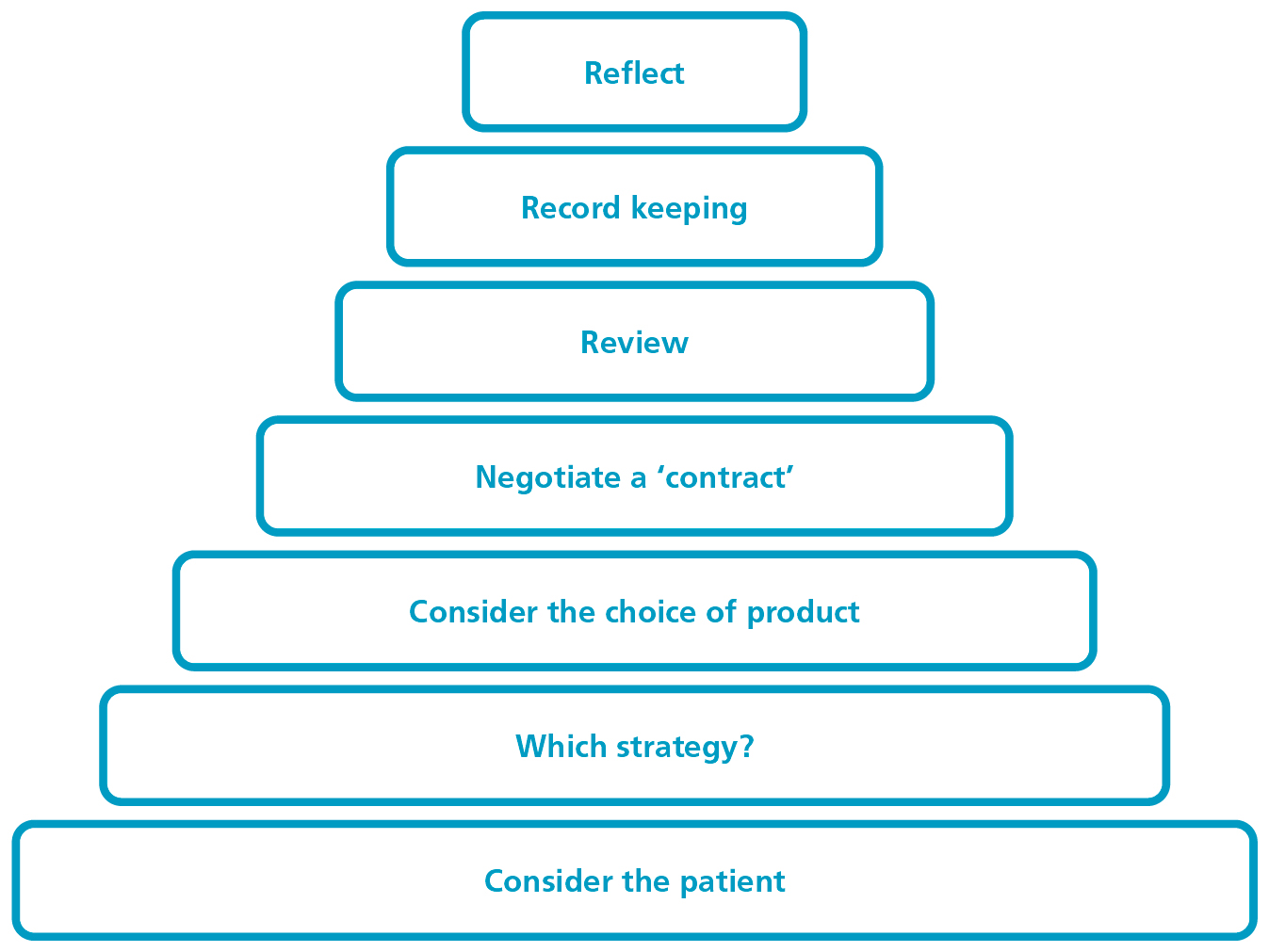

The RPS framework was designed to develop and refine the previous prescribing competency framework (Figure 1 shows the prescribing pyramid) published by the National Prescribing Centre (NPC) (Beckwith and Franklin, 2011).

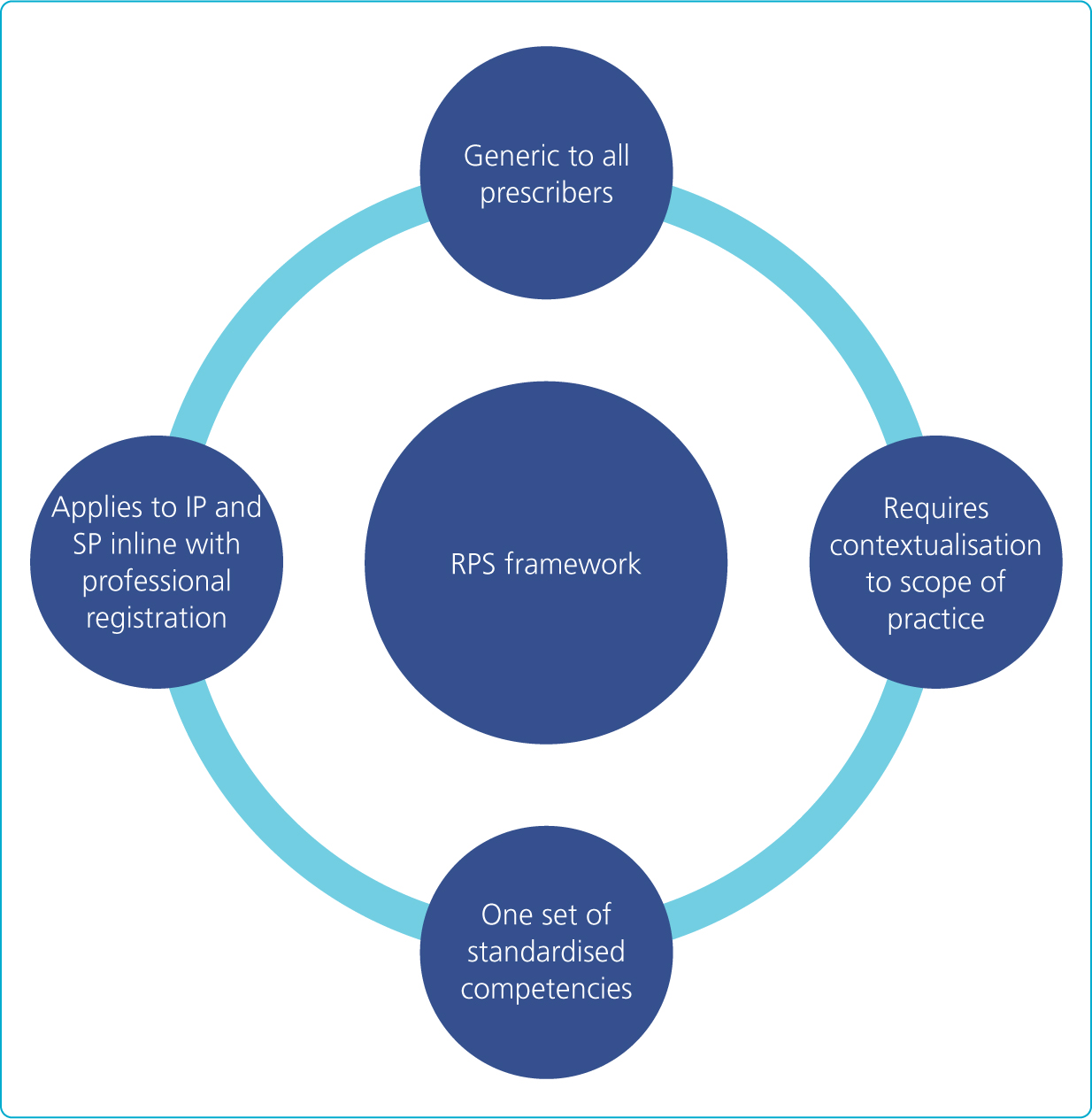

The prescribing competency framework, as laid out by the RPS in 2016 and updated in 2021, can be used by any prescriber at any point in their career to underpin professional responsibility for prescribing. It is the competence framework by which all higher education institutes must now educate and assess their NMP students against. It can also be used by regulators, professional organisations, and specialist groups to inform standards, policy, and professional expectations of prescribing registrants. It can also support newly qualified prescribers to develop by using self-assessment appraisal and structured feedback to develop into advanced prescribers. Core attributes of the framework are shown in Figure 3.

The RPS (2021) competency framework outlines what prescribing competence looks like. This is split into 10 competencies across 2 domains.

Within each of the 10 competencies there are statements which describe the activity or outcome that prescribers should be able to demonstrate. Central to all areas of the framework is the patient-centric approach (Table 1).

Table 1. RPS Domains and Competencies

| Domain 1: The Consultation | Competence |

|---|---|

| 1 Assess the Patient | |

| 2 Consider the options | |

| 3 Reach a Shared Decision | |

| 4 Prescribe | |

| 5 Provide Information | |

| 6 Monitor and Review | |

| Domain 2: Prescribing Governance | 7 Prescribe Safely |

| 8 Prescribe Professionally | |

| 9 Improve Prescribing Practice | |

| 10 Prescribe as Part of a Team |

Supervision and assessment

From 2005 up until 2019, to be able to complete the non-medical prescribing course individuals had to be supported by a designated medical practitioner (DMP). The criteria for the role of DMP was three years recent clinical experience, and they were often a GP, specialist registrar, clinical assistant or a consultant within an NHS trust, or other NHS employee that had the support of the employing organisation and could provide supervision, support and the opportunity to develop competence in prescribing practice. They would also be required to have experience in training or teaching and/or supervising practice (NMC 2006). This reliance on doctors to undertake supervision and assessment remained in place until 2019 when regulatory changes were brought about by the NMC in relation to student supervision and assessment (NMC, 2018a), and prescribing programmes (NMC, 2018b), HCPC and GPhC (2022). These changes allowed the RPS to devise and embed a competency framework for designated prescribing practitioners (DPP) which supported experienced non-medical prescribers of any profession to provide supervision and assessment to prescribing students (RPS, 2019).

Designated Prescribing Practitioner is an umbrella term now used by the RPS to define the named individual/individuals who are responsible for the prescribing student's clinical education and supervision. Depending on the registration of the student, this may be one person acting as DPP (for HCPC registered students, and out with the scope of this article) or two (as practice assessor and practice supervisor for NMC registered students).

Whilst there is variation across the professions, what remains is the openness to support from suitably qualified, experienced prescribers within their scope of intended prescribing practice.

Conclusion

As highlighted in this article, it has taken decades for nursing and nurse prescribing to evolve. Personally, I feel that the recent changes that have allowed us, as nurse prescribers, to act as practice assessors/supervisors is a positive change that has helped me to develop in my role by encouraging me as an assessor/supervisor which in turn has ensured that I develop a broad learning experience for my students. Concurrently allowing me to home in on and continue to understand the complexities and legalities, including the legalities of advertising within the context of prescribing in aesthetics. Students within their placement are encouraged to evidence experiences with other practitioners/pharmacies/GPs/specialist nurses etc. These episodes of student support have ensured that I keep my knowledge current and up to date with my prescribing practice, teaching and assssing which allows me to evidence this in my own revalidation.