Cosmetic procedures have a twofold impact, firstly, on the external part of the body that is shown to the world, and, secondly, the internal part, which is the individual's psyche and includes self-esteem, body image and confidence (Auer, 2018). Therefore, it is paramount for aesthetic practitioners to consider both the physical and psychological wellbeing of their patients. The risks of aesthetic procedures are often minimised by the way it is portrayed in the media. This causes patients to think it may be a ‘quick fix’ to more deep-seated psychological issues.

Body image development

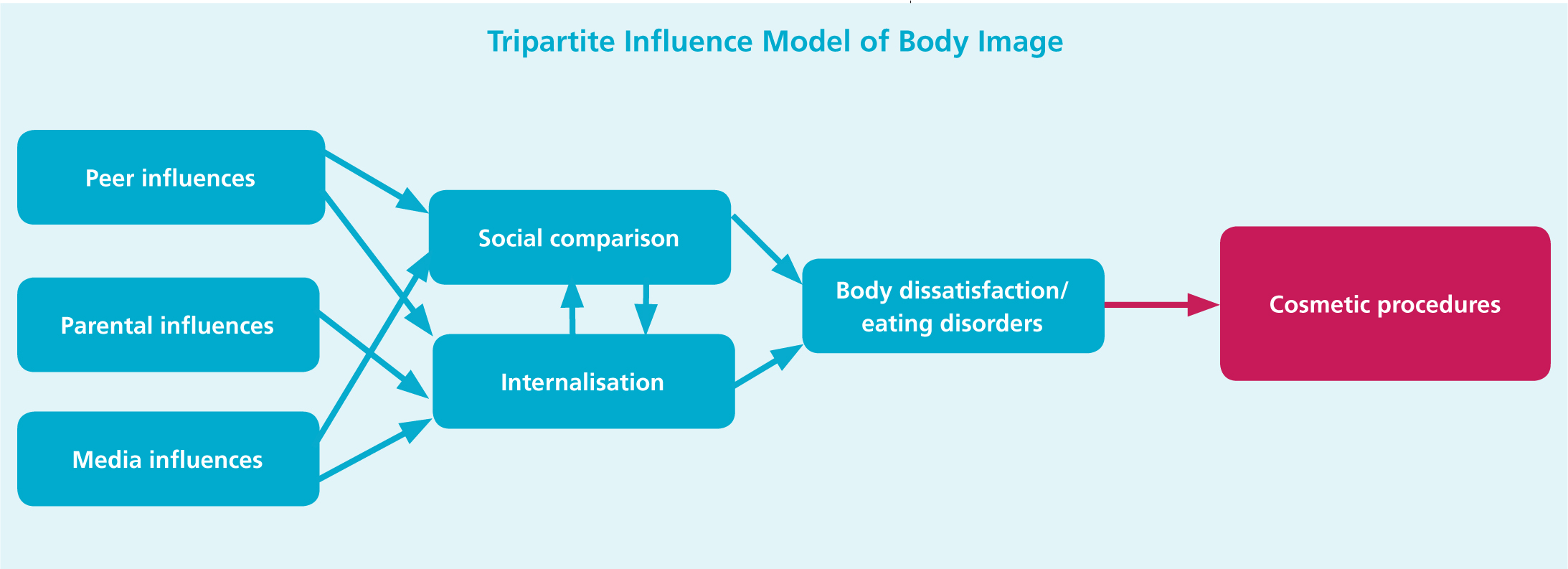

The key to understanding why specific individuals request cosmetic procedures lies in understanding how relationships with the body and body image are developed. Body image development is a complex psychological and physical process. It is impacted by a number of different factors from peer, parental and media influences.

Figure 1 indicates which factors contribute to body dissatisfaction, these can then lead to a patient seeking cosmetic procedures (Auer, 2018).

Figure 1. Tripartite Influence Model of Body Image

Figure 1. Tripartite Influence Model of Body Image

Parental influences

Attachment history and body image

Attachment history impacts whether someone develops a secure sense of self and positive self-esteem or whether they have an insecure sense of self and low self-esteem (Gilbert and Miles, 2002; Gerhardt, 2004; DeYoung, 2015). Secure attachment styles are associated with higher levels of self-esteem and more positive attitudes towards others, and comfort with both closeness and separation in relationships (Bowlby, 1988), whereas an anxious attachment style has been associated with body dissatisfaction and, therefore, a vulnerability to the internalisation of body ideals.

Higher attachment anxiety also leads a person to be more ‘other’-orientated, and thus susceptible to negative influences from the social environment and especially family (Menzel et al, 2011). This leads to some individuals being more vulnerable to the impact of media and societal pressures to look a certain way (Thorpe et al, 2004).

Shame as a driver for cosmetic procedures

Negative comments about one's appearance from parents, siblings and peers can contribute to shame-based processes. An individual may then be vulnerable to outside influences about how they look and relate to others. People may seek cosmetic procedures in the hope that if they look a certain way, they may then be able to ward off further comments (Lemma, 2009; Lemma, 2010). The cosmetic industry can portray cosmetic procedures as a way in which people can love themselves again. However, this may then cause individuals to seek out these procedures in the hope that they will be able to change that part of themselves they feel ashamed of (Northrop, 2012). It is important to note, if a discomfort with the body is connected with unconscious psychological processes for example shame, cosmetic procedures alone are unlikely to shift it. Assuming that others are judging you as offensive or unacceptable may give rise to feelings of shame; however, whether shame becomes an embodied feeling will depend on the fragility of one's sense of self, body image and attachment history. It is important to recognise when a patient may have experienced shame in their childhood, as this may be a critical factor in their decision to pursue cosmetic procedures.

The key to understanding why specific individuals request cosmetic procedures lies in understanding how relationships with the body and body image are developed

The key to understanding why specific individuals request cosmetic procedures lies in understanding how relationships with the body and body image are developed

Peer influences

There is a specific type of peer influence: namely conversations with friends that can lead to a more favourable attitudes towards cosmetic procedures (Sharpe et al, 2014). This is because the conversations focus attention towards appearance issues, reinforcing the importance of appearance and advocating for appearance ideals. Frequent appearance-related conversations with friends have also been associated with elevated body dissatisfaction (Auer, 2018). This can be explored by asking patients about their appearance preoccupation, how much they discuss it with their peers and how much of their times it consumes.

Media influences

There is immense pressure on individuals to conform to a specific appearance ideal (Locatelli, 2017). The media and, in particular, television programmes about cosmetic procedures influence an individual's attitudes towards it by affecting their own body dissatisfaction (Sharpe et al, 2014). If women compare themselves to idealised images in the media, ‘they will almost always find themselves lacking and become dissatisfied’ (Sharpe et al, 2014). There is a strong correlation between the viewing of cosmetic-related programmes and an interest in having cosmetic procedures. This makes sense, because the media normalises cosmetic surgery as being an ‘acceptable’ way to improve the appearance of one's body. The media and advertising campaigns have a responsibility to ensure the public are fully informed of the risks of undergoing any appearance related procedures. Terms like ‘nip and tuck’, ‘boob job’, ‘nose job’, and ‘freshening up’ (for facelift and eyelid surgery) seem rather benign, but what they do is minimise the perceived risks of surgery so that individuals are unaware of the invasive nature of some procedures (Auer, 2018).

Social comparison

Fear of negative evaluation from others

The perception of one's self in the mirror is constructed symbolically by meaning and experiences a person has throughout their life. It is not just someone's reflection that can result in potential shame-based feelings, but also the imagined effect that the reflection has on another person (Cooley, 1902). Self-concept is developed by having an imagined inner dialogue with those around us (Cooley, 1902). We try to imagine what others think of us, how they might judge us and how they might view our appearance. This is what gets played out when someone is seeking the opinions of others on how they look; this gauging of reaction is the very behaviour that individuals use in trying to assess how their appearance will be perceived by another.

Internalisation of beauty ideals

There is overwhelming pressure on women and, more recently, men, to conform to a particular beauty ideal that is portrayed by the media and magazines (Auer, 2018). Questions should be asked about whether cosmetic procedures are truly a freedom choice (Wijsbek, 2000). This becomes evermore prevalent when a practitioner performing these procedures is assessing their patient's motivation and expectations. We now live in a consumer-focused society, where one's appearance assumes more importance than ever (Auer, 2018). Higher anxiety means that an individual is more susceptible to internalising beauty ideals portrayed in the media, and to negative cultural, parental and peer influences (Hardit and Hannum, 2012). An individual with low self-esteem is more susceptible to internalising beauty ideals. They will be impacted by conversations with friends and family about their body and the media's normalisation of cosmetic surgery (Menzel et al, 2017). These factors then have a further impact by causing a favourable attitude towards cosmetic procedures (Menzel et al, 2017)

Supporting the physical and psychological wellbeing of patients

Discourse between the practitioner and patient

Aesthetic practitioners need to bear in mind that how and what they say to patients will have an influence in how the patients feels and whether or not they decide to proceed. Often, patients can be in vulnerable psychological states and, therefore, it is important for the practitioner to consider this in consultations (Parker, 2009), especially when it comes to helping patients decide whether or not to have a particular procedure. Wherever possible, practitioners should avoid agreeing or disagreeing with patients about how they look. This prevents additional procedures being requested or suggested, which can lead to difficulties postoperatively if the patient is unhappy (Blum, 2003). This also better manages patient expectation and remains in line with the patient's original request.

Exploring expectation and motivation

A number of factors will contribute to an individual's decision to alter their appearance. It is imperative the aesthetic practitioner has a way of exploring this with the patient. This enables the patient to make a more informed choice about whether or not the requested procedure is likely to achieve the expected outcome. Often, the timing of the requested procedure can provide the practitioner with important information about what might be going on in the patient's life in terms of significant life events, etc. The practitioner will be best placed if they consider both the psychological and physical expectations from the procedure. The physical (visible) is what external change the patient is expecting. The psychological (internal) is the more challenging one to fully address. This may include aspects like increasing self-esteem and confidence, and sometimes a hope that the individual will be less preoccupied with their appearance. This last factor is important for the practitioner to consider, because the level of preoccupation at the time of the requested procedure may be an indicator of body dysmorphic symptoms. This will certainly warrant further exploration, either by the practitioner or another suitably qualified mental health professional.

Identifying signs of body dysmorphia

There is a high prevalence of body dysmorphia amongst patients seeking cosmetic procedures (Sarwer, 2002). Studies indicate that performing cosmetic procedures on this patient group is often contraindicated as they are more likely to be dissatisfied postoperatively. If a procedure is performed it may well just shift the preoccupation to different area of the body or increase the overall preoccupation (Cook, Rosser and Salmon, 2006; Castle et al., 2004). Aesthetic practitioners therefore need to be able to identify those patients who are presenting with symptoms of body dysmorphia.

Psychological screening tools

One way in which aesthetic practitioners can support their practice and how they assess patient suitability is to include a body image screening questionnaire (Paraskeva et al, 2014). This then helps to open up discussions around how patients feel about their bodies. However, before including these questionnaires, it is important that practitioners are suitably trained to interpret the outcomes. They also need to have an appropriate referral pathway if they do come across a patient that requires additional support.

Conclusion

There are many individuals who gain benefit from undergoing cosmetic procedures.

However, there are also many vulnerable individuals seeking cosmetic procedures and practitioners need to be able to identify this patient group. This article hopes to provide insight into the many factors that underlie body image development and contribute to an individual's decision to seek cosmetic procedures, as opposed to other treatments. It is crucial that patients are given time to discuss with their practitioner their motivation and expectation from the proposed procedure. This helps both parties understand whether the anticipated outcome, both physical and psychological is realistic.

Key points

- Understanding body image development is paramount when assessing a patient's suitability for a cosmetic procedure

- Having an appropriate referral pathway in place supports good, ethical practice

- Exploring motivation and expectations of patients helps to ensure good outcomes for all.

CPD reflective questions

- How do you currently explore the motivation and expectations of patients?

- How do you assess whether somebody has appearance related distress that may benefit from other treatments for example: psychological therapy?

- How do you feel about your body image? Are you able to judge whether your appearance concerns are within what would be considered healthy/normal?