The World Health Organization (WHO) has defined obesity as abnormal or excessive fat accumulation that may impair health (WHO, 2000; 2019). The fundamental cause of obesity is an energy imbalance between calories consumed and calories expended. Globally, there has been an increased intake of energy-dense foods that are high in fat and carbohydrates, accompanied by a decrease in physical activity with increasingly sedentary lifestyles (WHO, 2019).

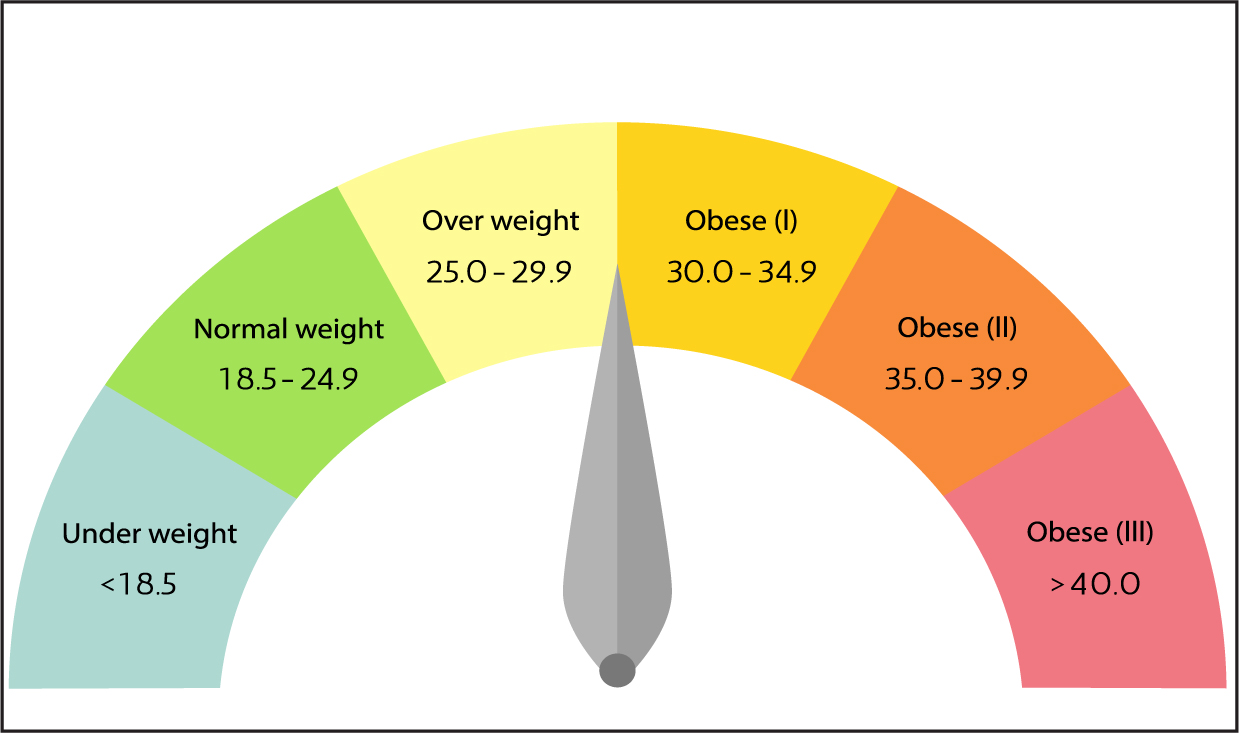

The most common and convenient measurement of obesity used is body mass index (BMI). BMI is calculated by dividing a person's weight in kilograms by their height in metres squared. The result produced then falls into a number of classifications (WHO, 2019). A BMI below 18.5 kg/m2 is classed as underweight, between 18.5 and 25 kg/m2 is considered healthy and between 25 and 30 kg/m2 is regarded as overweight. A BMI over 30 kg/m2 is classed as obese, with this range then being further divided into three obesity classes (Figure 1).

Obesity rates have been increasing worldwide, and it is recognised as a disease and a health issue by various global organisations and regulatory bodies:

‘Obesity is a chronic disease, prevalent in both developed and developing countries and affecting children as well as adults’.

‘Obesity is recognised as a chronic clinical condition and is considered to be the result of interactions of genetic, metabolic, environmental and behavioural factors, and is associated with increases in both morbidity and mortality’.

‘Overweight and obese people are a majority today in the OECD area. The obesity epidemic continues to spread, and no OECD country has seen a reversal in trends since the epidemic began’.

‘Obesity is a progressive disease, impacting severely on individuals and society alike. It is widely acknowledged that obesity is the gateway to many other disease areas’.

Obesity is associated with multiple comorbidities, affecting not just mechanical systems within the body, but also metabolic and mental health (Jarolimova et al, 2013). Mechanical comorbidities include poor physical functioning, incontinence, chronic back pain and sleep apnoea, whereas metabolic comorbidities include asthma, gallstones, infertility, various cardiovascular diseases, as well as type 2 diabetes, thrombosis and some cancers. Mental health comorbidities can include depression and anxiety (Jarolimova et al, 2013).

Management of obesity

There are many personal benefits to weight loss. If a person is overweight or obese, a loss of 5–10% of total body weight can have a number of health advantages, including a reduction in risk for type 2 diabetes (Knowler et al, 2002; Asif, 2014), reduction in cardiovascular mortality (Li et al, 2014), improvements in blood pressure (Wing et al, 2011) and improvements in health-related quality of life (Warkentin et al, 2014). There are also benefits for wider society. In the UK, in 2006–2007, ill-health due to being overweight or obese cost the NHS £5.1 billion (Scarborough et al, 2011). In the UK, there are three EMA-approved medications to aid weight loss: orlistat (Xenical, Alli), liraglutide (Saxenda) and naltrexone in combination with bupropion (Mysimba). They all work in different ways. Orlistat reduces fat digestion, bupropion/naltrexone reduces appetite and liraglutide slows gastric emptying, increasing feelings of fullness.

Orlistat

Orlistat is a lipase inhibitor and works by reducing the amount of fat that is digested. The undigested fat, approximately one-third of that eaten, is not absorbed by the body and is passed through the digestive system. Orlistat tablets come in 60 mg and 120 mg capsules (British National Formulary, 2018). The 60 mg capsule may be purchased from pharmacies and is indicated for weight loss in adults with a BMI of at least 28 kg/m2. The 120 mg capsule is available by prescription for those with a BMI of either at least 30 kg/m2 or at least 28 kg/m2 with associated risk factors (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), 2019a). For it to work effectively, it should be taken in conjunction with other lifestyle changes, such as a low-calorie diet and increased physical activity. A low-fat diet is also recommended, as this will help to avoid some of the gastrointestinal side effects, such as oily stools and faecal incontinence.

Naltrexone with bupropion

Both naltrexone and buproprion are approved separately for use for conditions other than obesity. Naltrexone is usually given to block the effects of narcotics or alcohol in people with addiction problems, while buproprion is an antidepressant and smoking-cessation aid. The combination of the two drugs seems to work by affecting brain circuitry in the appetite and reward centres (Bersoux et al, 2017).

The combination (Mysimba) is an oral tablet and again is most effective when used in conjunction with a reduced-calorie diet and increased physical activity. It is prescribed for people with a BMI of either at least 30 kg/m2 or at least 27 kg/m2 with one or more weight-related comorbidities (NICE, 2019b).

Its approval was not without controversy (Hawkes, 2014), with Prescrire (2015) commenting that the disproportionate risk of adverse events could not be justified by the modest extra weight loss that a person might achieve through taking the combination.

Liraglutide

The third approved drug is liraglutide, a prescription-only, once-daily subcutaneous injection, and the main focus of this article. It is the active ingredient of Saxenda and is a human glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1). It was originally approved for use in the treatment of type 2 diabetes, and in 2015 the EMA approved its use in weight management (EMA, 2015).

Again, it should be taken in conjunction with a reduced-calorie diet and increased physical activity for long-term weight management. It may be prescribed for individuals with either a BMI of either at least 30 kg/m2 or at least 27 kg/m2 alongside another weight-related illness, such as high blood pressure, type 2 diabetes or dyslipidaemia (NICE, 2019c).

Mechanism of action

GLP-1 stimulates insulin secretion and inhibits glucagon secretion, contributing to preventing glucose spikes following meals. It also slows down the passage of food from the stomach into the intestine, causing the user to feel fuller for longer after a meal, thus reducing appetite and food intake (Holst, 2007).

Dosage and administration

The recommended dose of liraglutide is 3 mg daily (NICE, 2019c). It should be injected subcutaneously into the abdomen, thigh or upper arm at any time of day, without regard to the timing of meals. It is recommended that the drug is initiated at 0.6 mg per day for 1 week and increased incrementally at weekly intervals until the full 3 mg dose is reached (NICE, 2019c). Dose escalation is recommended to minimise the likelihood of gastrointestinal symptoms (Pi-Sunyer et al, 2015). Discontinuation should be considered if a dosage is not tolerated for 2 consecutive weeks (NICE, 2019c).

Once the full dose has been reached, the change in body weight should be evaluated after 12 weeks. If, at this point, at least 5% of the initial bodyweight has not been lost, the treatment should be discontinued, as it is unlikely that continued treatment will result in clinically meaningful and sustainable weight loss (NICE, 2019c).

Pi-Sunyer et al (2015) looked at liraglutide for weight management in a large, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled international trial. There were 3731 participants, 45% of whom did not have diabetes mellitus, but 60% had prediabetes. At the end of the study, the liraglutide group had lost a mean of 8.4 kg, versus 2.8 kg in the placebo group. Additionally, 63% of the liraglutide group has lost at least 5% of body weight, versus 27% in the placebo group, and 33% lost at least 10% of body weight, versus 10% in the placebo group.

Side effects

Studies have shown that the majority of side effects experienced were mild to moderate gastrointestinal symptoms that were not severe enough to lead to discontinuation of treatment (Lean et al (2014). Side effects occurred during the initial phase of dose escalation reduced within a few days or weeks of treatment (Pi-Sunyer et al, 2015). The most common side effects are nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea and constipation, while common side effects include hypoglycaemia, insomnia, dizziness, dysgeusia, dry mouth, dyspepsia, gastritis, gastro-oesophageal reflux disease, flatulence, abdominal distension, fatigue, increased lipase, increased amylase and cholelithiasis (British National Formulary, 2018). There may also be reactions at the site of injection.

Cautions and contra-indications

As with all medicines, there are a number of cautions and contra-indications for liraglutide use (Box 1). These should be discussed fully with the individual before commencement on the medication. According to the BNF, liraglutide is contra-indicated in diabetic gastroparesis, inflammatory bowel disease andsevere congestive heart failure, and Saxenda in particular is contra-indicated in concomitant use with other products for weight management, patients aged 75 years or over and obesity secondary to endocrinological or eating disorders.

Expectations and results

Realistic weight-loss expectations

When a patient begins liraglutide, an important first step is to set realistic expectations for weight loss. The results of the SCALE clinical trial by Pi-Sunyer et al (2015) can be a useful indicator. The researchers found that, across all patient groups studied, superior weight loss was achieved with liraglutide versus placebo when used as an adjunct to diet and exercise, with an average weight loss of 9.2% compared with 3.5%. Compared with controls, more than three times as many liraglutide patients lost at least 10% loss of their starting weight, and more than twice as many lost more than 5% of their initial weight (Table 1).

| Metric | Liraglutide | Control |

|---|---|---|

| Patients who lost at least 10% of initial body weight | 33% | 10% |

| Patients who lost at least 5% of initial body weight | 63% | 27% |

| Reduction in weight loss | 8.0% | 2.6% |

| Average loss of body weight from baseline | 9.2% | 3.5% |

Results of an additional 2-year study showed that, when comparing liraglutide with orlistat, the group that received liraglutide achieved a significantly greater weight loss (Ladenheim, 2015). Studies have shown that liraglutide (3.0 mg/day) in combination with a low-calorie diet and increased physical activity resulted in significantly greater weight loss in overweight and obese adults with type 2 diabetes than in those receiving placebo (Wadden et al, 2015)

Working with patients to improve results

It is important that healthcare professionals work together with their patients and develop a plan that not only helps them stay on track, but also keeps them motivated throughout their weight-loss journey. Attainable goals should be set within realistic and achievable timeframes.

In addition to setting goals and being consistent with medication, achieving a long-term lifestyle change requires that patient plans include healthy eating and staying active. Activities that the patient enjoys should be added to the plan and included as part of a daily routine.

Health markers and progress should be tracked to help encourage patients. There are various online support programmes that can also help. Patients taking Saxenda have access to the manufacturer's own complimentary online support programme, WeightJourney (Novo Nordisk), that aims to help patients reach their goals by focusing on small steps. WeightJourney sends weekly emails, provides relevant advice on healthy eating and exercise and may be connected with other tracking apps.

Conclusion

It is clear that obesity management is not only important for individuals themselves, both physically and mentally, but also for the NHS and society as a whole. It must be emphasised that, before beginning treatment, patients should be aware of all side effects and contraindications, as well as have realistic expectations when it comes to weight-loss goals—which will help maintain motivation. Patients should be made aware that these medications only work when used in conjunction with a low-calorie diet, and increased physical activity should be encouraged to achieve optimum results.