The process of generalised sweating, under normal circumstances, is a means by which the body affects thermoregulation. This vital role of the human body is under the control of the hypothalamus.

It is primarily the anterior nucleus, but also the supraoptic region within the hypothalamus, that is involved in thermoregulation. Simplistically, these areas within the hypothalamus regulate, via the sympathetic nervous system, sweating and cutaneous vasodilation or shivering and cutaneous vasoconstriction, as required, to thermostatically maintain the body's temperature, within 1–2 °C of 37 °C (Crumbie, 2020). Hyperhidrosis is a disorder that is characterised by excessive sweating beyond physiological requirements.

The body also produces sweat to help the hands maintain a good grip, which is a useful function in peoples' daily lives. Palmar–plantar sweating (the hands and feet) is controlled mainly via the cortex and limbic systems, and the nerve pathways here are the same as in thermoregulation. However, the hypothalamus itself is also a nucleus for the limbic system, so stress-related palmar sweating can result in whole-body sweating, and, subsequently, a generalised rise in body temperature can worsen palmar–plantar sweating (Rystedt et al, 2016).

The body sweats through sweat glands, also referred to as sudoriferous or sudoriparous glands, which are found throughout the skin (dermis). There are different types of sweat glands: eccrine and apoeccrine glands. These glands lie within the dermis and help cool the body, producing normal salty sweat, and can produce up to 3 litres of odourless fluid per hour (Lenefsky and Rice, 2018). Meanwhile, apocrine glands are usually associated with hair follicles and are found mainly in the groin, perianal and axilla areas. The sweat that they excrete contains pheromones within an oily substance, giving rise to an individual's sweaty odour. Apocrine glands begin to function at puberty, driven by sex-hormone stimulation (Baxter, 2020).

Hyperhidrosis

Hyperhidrosis can be classified as either primary, the most common type, or secondary, which will be detailed below.

Primary hyperhidrosis

Primary hyperhidrosis typically starts in childhood or at puberty. Although it can improve with age, it may persist for the whole of the patient's life, and both males and females are equally affected (British Association of Dermatologists (BAD), 2018). The exact cause of primary hyperhidrosis is unknown. Primary hyperhidrosis may be familial, with transmission of the disorder as an autosomal trait; however, a gene locus has not been identified, although hyperhidrosis is a feature of some rare inherited diseases (Kaufmann, 2003).

Botulinum toxin type A is usually the most effective non-surgical treatment, primarily for focal axillary hyperhidrosis, but it can also treat plantar and palmer hyperhidrosis

Botulinum toxin type A is usually the most effective non-surgical treatment, primarily for focal axillary hyperhidrosis, but it can also treat plantar and palmer hyperhidrosis

Primary hyperhidrosis can be subdivided into focal and general classifications. Primary hyperhidrosis usually affects bilateral and symmetrical areas: the hands, feet, axilla, groin and inframammary fold. Generalised hyperhidrosis can affect the whole body, including the trunk, craniofacial and, occasionally, the groin and gluteal areas. In children, it tends to be the hands and the feet that are affected, with the axilla areas not involved until puberty. The face can also be affected, where the condition can manifest in a type of persistent blushing alongside the excessive sweating.

Secondary hyperhidrosis

Secondary hyperhidrosis is primarily generalised and asymmetrical, affecting the whole body. Most often, it can be an outward sign of an underlying condition, disease or hormonal imbalance, including neuropathy, hyperactive thyroid, diabetes, disorders of the pituitary gland, gout, menopause, obesity, brain or endocrine tumours and alcoholism (BAD, 2018). It can also present as focal and symmetrical, such as in the case of spinal injury or stroke.

Generalised secondary hyperhidrosis can also be associated with cases of infection, neoplasia, metabolic and endocrine disorders, high catecholamine states and neurological problems. Certain drug therapies can also predispose to secondary hyperhidrosis, including propranolol (a beta blocker), physostigmine and pilocarpine (used in the treatment of glaucoma), as well as fluoxetine, venlafaxine and tricyclic antidepressants.

There are two rare conditions in which sweating is a symptom. One is Frey's syndrome, a rare neurological disorder following damage to the facial nerve. The other is Greither's disease, a rare inherited skin disorder that causes thickening of the palmar–plantar skin, with a major symptom being excessive sweating of both the hands and feet.

Many women experience postmenopausal hyperhidrosis. This can be the diagnosis for women who have generalised hyperhidrosis around the age of 50, even when an oestrogen supplement is provided.

Anxiety can also trigger or exacerbate excessive sweating; sometimes the individual can be stressed about the excessive sweating, creating an unfortunate vicious circle.

The consultation process

When the patient attends clinic, they will have arrived via one of two clinical pathways. They may be a medical referral from their GP following a diagnosis of primary hyperhidrosis, which can be made when the patient has fulfilled various criteria. These criteria are: extreme sweating for more than 6 months; episodes occurring at least once a week; symmetrical and bilateral sites of sweating; an absence of sweating at night; onset of sweating from age 25 years or under; a possibility of positive familial history; and the sweating being described as disruptive to their day-to-day life. Alternatively, they will have independently researched an aesthetic clinic in search of a treatment that is delivered for excessive sweating.

Whichever pathway brings the patient to clinic, at consultation, a full medical, social and aesthetic history must be taken and fully documented. Aesthetic practitioners are responsible for the safety and quality of care that is provided (Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC), 2018); Therefore, the practitioner must be sure that the patient's hyperhidrosis is primary and not secondary. If they are self-referred and there are any doubts at all regarding their type of hyperhidrosis, the patient must be referred on to their GP.

As hyperhidrosis is classified as a medical disorder (National Organization for Rare Disorders, 2021), when it is diagnosed, it must be treated as such. To provide treatment for a disease and disorder in private practice, the practitioner and clinical premises must be registered by the appropriate regulatory body for the country in which they practice (Health and Safety Executive (HSE), 2021). In England, this is the Care Quality Commission (CQC), in Wales, it is Health Inspectorate Wales (HIW) and, in Scotland, all clinics have to be registered with Healthcare Improvement Scotland (HIS). Treating a diagnosed medical disease or disorder without adhering to the above regulatory standards could place the practitioner in breach of ethical, professional and regulatory standards (NMC, 2018).

However, if the patient has independently sought out treatment for excessive sweating that is impacting negatively on their lives socially, emotionally and/or professionally, which may, ultimately, impact their mental wellbeing, then this is not necessarily classed as a medical treatment. Therefore, in this instance, there is not a requirement for the clinic premises to be registered, which is, admittedly, a grey area.

During consultation, the patient will often describe being frequently disturbed or bothered by their sweating: it may interrupt activities within their daily, social and work life. They may have to avoid wearing certain fabrics, along with different types and colours of clothing. They may tell of the necessity to take multiple showers per day or having to take a change of clothes with them to work or to social events. As previously mentioned, this often greatly impacts their emotional and mental wellbeing, potentially resulting in feelings of anxiety, embarrassment, sadness, anger and hopelessness (Lenefsky and Rice, 2018). In the US, a study by Doolittle et al (2016) showed that 75% of respondents in a survey, completed by patients with hyperhidrosis, indicated that the excessive sweating they were experiencing led to ‘negative effects on their social life, and their emotional and mental health’.

Hyperhidrosis presents potential daily challenges to the individual. In fact, it can impinge on the patient's life so drastically that decisions as variable as what they decide to wear in the morning to what career path they choose can be affected.

Once a diagnosis is confirmed, ascertaining some measure of the degree to which hyperhidrosis is impacting on the patient's life is extremely important. There are diagnostic tools available that can be incorporated into the consultation process to help with this, such as the Hyperhidrosis Disease Severity Scale (HDSS) (Box 1) and the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) questionnaire, among others.

Box 1.Hyperhidrosis Disease Severity Scale

- My (underarm) sweating is never noticeable and never interferes with my daily activities Score: 1

- 2. My (underarm) sweating is tolerable but sometimes interferes with my daily activities Score: 2

- 3. My (underarm) sweating is barely tolerable and frequently interferes with my daily activities. Score: 3

- 4. My (underarm) sweating is intolerable and always interferes with my daily activities Score: 4

(International Hyperhidrosis Society, 2007)

When using the HDSS scale in the consultation, areas that are problematic for the patient in relation to their excessive sweating should be inserted as required. A score of 3 or 4 on this scale indicates severe hyperhidrosis, whereas a score of 1 or 2 is moderate or mild. This diagnostic aid can be again used post-treatment to assess any improvements. A 1-point fall on the scale equates to a 50% reduction in sweating, while 2 points equates to an 80% reduction in sweating (International Hyperhidrosis Society, 2007). However, it must be noted that this is a basic scoring tool (Jones-Diette et al, 2017).

The Hyperhidrosis Quality of Life Index (HidroQOL) is the most comprehensive and straightforward tool and covers disease-specific quality of life dimensions that are relevant to the patient. It is detailed in Table 1 (Jones-Diette et al, 2017).

Table 1. Hyperhidrosis Quality of Life Index (HidroQOL)

| Domain one |

| 1. My choice of clothing is affected |

| 2. My physical activities are affected |

| 3. My hobbies are affected |

| 4. My work is affected |

| 5. I worry about the additional activities in dealing with my condition |

| 6. My holidays are affected (for example, planning and activities) |

| Domain two |

| 7. I feel nervous |

| 8. I feel embarrassed |

| 9. I feel frustrated |

| 10. I feel uncomfortable physically expressing affection (for example, hugging) |

| 11. I think about sweating |

| 12. I worry about my future health |

| 13. I worry about people's reactions |

| 14. I worry about leaving sweat marks on objects |

| 15. I avoid meeting new people |

| 16. I avoid public speaking (for example, presentations) |

| 17. My appearance is affected |

| 18. My sex life is affected |

Note: Patients should answer ‘very much’ (2 points), ‘a little’ (1 point) or ‘no, not at all’ (0 points) for each statement and a total score should be calculated

(Jones-Diette et al, 2017)When using a tool such as the HidroQOL questionnaire, comparing a patient's answers before and after their specific hyperhidrosis treatment will provide an indication to the treatment's success.

Treating hyperhidrosis

Antiperspirants

The first avenue of treatment for localised hyperhidrosis is antiperspirants, especially for excessive sweating in the axilla area. The active ingredients usually found in commercially available antiperspirants are aluminium chloride, aluminium chloride hexahydrate and aluminum zirconium tetrachlorohydrex. A stronger topical formula, aluminium chloride hexahydrate 20%, can be prescribed and applied to the axilla area, along with the palms, the soles of the feet, the submammary area, groin and craniofacial regions. It is available as a spray, gel, wipe or a roll-on solution to the patient, which should be applied to dry skin at night-time and be used for an initial period of 6 weeks and observed for efficacy (British National Formulary (BNF) and National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), 2021a; 2021b). The most common reported side effect with this treatment is skin irritation. If this occurs, frequency of application can be reduced, or the amount of product used at each application can be reduced. Additionally, a mild topical corticosteroid, such as hydrocortisone, can be prescribed if required and used alongside the treatment.

Iontophoresis

For those who present with palmoplantar hyperhidrosis, iontophoresis is a non-invasive treatment that can be successful for 70–80% of patients (Hyperhidrosis UK, 2021). The treatment involves a specialised machine that passes a low-voltage direct electrical current through the skin via electrodes on either the hands or feet while they are immersed in a shallow amount of tap water.

Treatment with iontophoresis usually takes approximately 20 minutes for the hands and 30 minutes for the feet. It normally requires seven treatments over a 4-week period to initially achieve control of the hyperhidrosis, with a maintenance treatment every 1–2 weeks, depending on the needs of the individual patient. There are iontophoresis machines now available that patients can purchase and use at home.

Medication can also be added to the tap water at the time of the treatment, such as glycopyrronium bromide, which is an anticholinergic (BAD, 2016) and licenced for this indication (Electronic Medicines Compendium (EMC), 2016). The electrical current that is generated helps to push the medication through the skin via polarity. Only one site should be treated in this instance per treatment, with two sites treatable in 24 hours. Glycopyrronium bromide is a prescription-only medicine (POM) and, as such, must only be used with in clinic iontophoresis treatments. A study by Doliantitis et al (2004) concluded that iontophoresis treatments undertaken with the addition of glycopyrronium bromide to the tap water gave significantly superior results compared with treatments undertaken with tap water alone.

Botulinum toxin type A

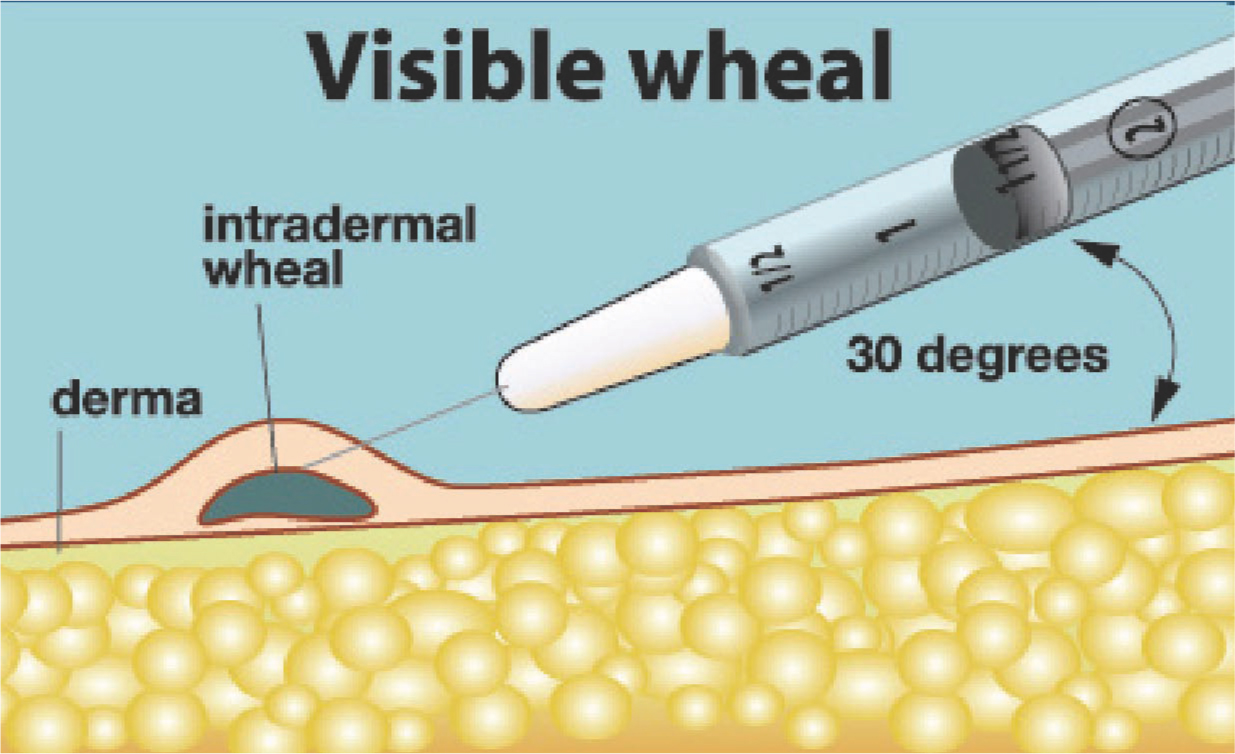

In the author's experience, botulinum toxin type A (BTX-A) is the most effective non-surgical treatment, primarily for focal axillary hyperhidrosis, but it is also used successfully to treat plantar and palmer hyperhidrosis. It is injected superficially intradermally, causing denervation by inhibiting the release of acetylcholine from the sudomotor synapses (Schlereth et al, 2009). The full effect of sweating reduction will usually be seen at around 14 days post-treatment, and, on average, results last for 4–12 months. BTX-A is licenced for use in treating hyperhidrosis in the axillary area that is unresponsive to topical antiperspirants or other antihidrotic treatments, but it is an off-label indication when used in plantar–palmar treatments.

When treating hyperhidrosis with BTX-A, the total amount of units to be used per area per treatment varies. When treating a new patient for this indication, it is always advisable, especially for a practitioner who is not experienced treating this modality, to follow the manufacturer's prescribing guidelines for the regular clinical neurotoxin. Many practitioners will slightly hyperdilute their BTX-A for this indication to assist with spread/diffusion and targeting as many sweat glands as possible within the area that is being treated.

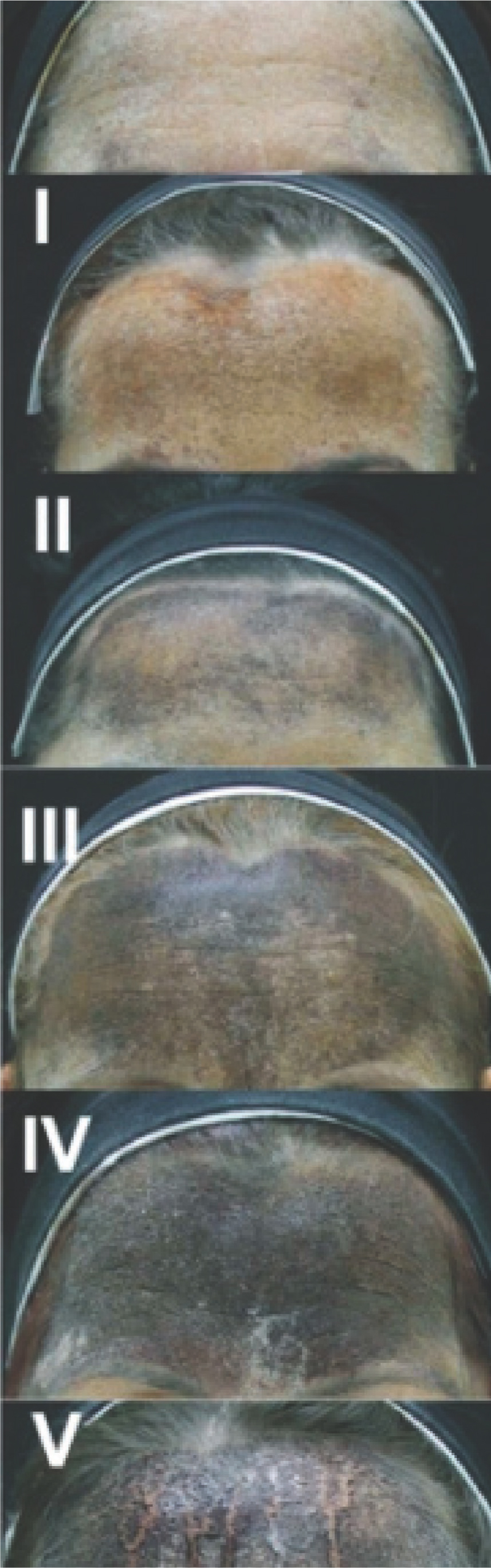

To ascertain where the patient is sweating most profusely within the axillary area, practitioners can undertake the Minor's starch–iodine test. Prior to undertaking the test, thoroughly cleanse and dry the skin. Next, apply the iodine solution to the axillary area and let it dry, then a starch powder should be lightly applied using a cotton wool ball or light brush (corn starch used for cooking would work). Any sweat present causes a chemical reaction, turning the light brown iodine a dark purple colour, thus clearly marking the areas of hyperhidrosis. The area of excessive sweating should be outlined with a dermographic pen or surgical marker. Photographs should be taken and recorded in the patient's notes. The Intensity Visual Scale (Figure 1) is a classification that can be used to document the intensity of the colour from the Minor's test and, therefore, the degree of hyperhidrosis.

Figure 1. Intensity Visual Scale

Figure 1. Intensity Visual Scale

The starch/iodine area should be cleaned again prior to treatment, leaving the marked treatment area as your guide. As previously mentioned, when treating, injections are kept superficial, and it is ideal to see a visible wheal (Figure 2) at each injection site.

Figure 2. Hyperhidrosis treatment

Figure 2. Hyperhidrosis treatment

To allow for diffusion, injections should be kept approximately 1.5–2.0 cm apart. Each injection point may be marked prior to treatment, but, if so, avoid injections directly through the marked dot to ensure that there is no carriage of ink into the dermis.

A review should be undertaken at week 2-4 to ascertain if there is any ‘breakthrough’ sweating. If there is, these areas should be treated as before.

Treating the palmar–plantar areas with BTX-A is an uncomfortable experience for the patient and carries with it a higher degree of potential side effects following treatment. When treating palmer hyperhidrosis, only one hand should be treated at a time, leaving 2-4 weeks between each appointment, with the non-dominant hand treated first. When treating the hands, the side effects can be bruising, reduced sensation in the fingers and finger motor function can be reduced.

MiraDry

MiraDry has been shown to be a safe, successful, permanent solution to excessive sweating that was given US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) clearance in 2015, and it is now available as a treatment in over 50 countries around the world (International Hyperhidrosis Society, 2020).

MiraDry uses thermal energy and microwave-based technology to selectively heat the area between the skin and underlying fat, resulting in the localised thermolysis of sweat glands in the area treated (Hong et al, 2012). It can be used to treat excessive sweating of the axilla and palmar–plantar areas, with some clinics also treating the back and chest areas. On average, it offers an 82% reduction in sweating (International Hyperhidrosis Society, 2020).

Oral anticholinergics

Oral anticholinergics are a group of drugs that can be prescribed for the systemic treatment of hyperhidrosis. They work by blocking the release of acetylcholine at the neuromuscular junction, and so rendering the sweat glands inactive. Unfortunately, as they are systemic, they work in other areas of the body, so side effects are common and include: dry mouth, dry eyes, difficulty with urination, constipation and headaches (Cruddas and Baker, 2017). Therefore, these drugs are not generally well tolerated. The two drugs most commonly prescribed are oxybutynin (Lyrinel), which is a modified release drug and the best tolerated, and glycpyrronium bromide (Robinul).

Endoscopic thoracic sympathectomy

When all else fails, surgery is the final treatment option. Patients must be carefully selected for endoscopic thoracic sympathectomy (ETS) and educated regarding its possible limitations and side effects. There have been frequent and irreversible side effects documented following this procedure, both acute and chronic, to the point that this surgery is now banned in Sweden (Rystedt et al, 2016). The most commonly reported side effect is compensatory sweating.

Conclusion

Primary focal hyperhidrosis is, for many, a life-altering condition that affects the individual physically, socially and psychologically. Many of the patients who are seen in aesthetic clinical practice want to look and, ultimately, feel better about themselves as they go about their busy and stressful daily lives. This is especially true for the patient who presents to the practitioner in clinic with excessive sweating that they have been unable to control. The medical practitioner has the opportunity to reassure and educate them about the fact that there are additional and often more successful treatments available. The practitioner can either provide those treatments or refer on, if specialist help is required.

Key points

- To treat hyperhidrosis, the aetiology of both primary and secondary hyperhidrosis should be understood, and the practitioner should appreciate what the compounded effect of such a condition can have on an individual's daily life

- Practitioners must understand when and how to safely treat each indication (axilla, palmar, plantar, etc), while providing continuous education and supporting the patient before, during and following any treatment

- The recognised, specific clinical training that is required must be undertaken prior to performing each of the treatments for hyperhidrosis.

CPD reflective questions

- How do dosage, dilution and diffusion affect botulinum toxin treatments?

- Research the manufacturer's recommended dosages for the various botulinum toxin type As that are licenced for the treatment of hyperhidrosis in the UK

- How do ‘tap water’ iontophoresis treatments work?

- What methods of anaesthesia can be employed prior to treating palmar plantar hyperhidrosis?