Cellulite is a ubiquitous, dimpled or bumpy texture on the buttocks and thighs that presents in the vast majority of post-pubescent females, as well as some males. In fact, it is so omnipresent that it is not classified a disease or medical issue; sometimes, it can simply be considered as aesthetically displeasing to its possessor and is generally considered a cosmetic problem. With societal norms shifting toward acceptance of all body types, sizes and previously perceived imperfections, treatments to improve the appearance of cellulite may be becoming outdated. Wall Street Journal reported that ‘there is finally innovation to report in the cellulite treatment category, but it comes at a time when perceptions of this supposed imperfection are changing’ (Valdesolo, 2021).

Social media may help to persuade people to consider cellulite as normal and acceptable. However, in the author's opinion, the search for cellulite solutions is here to stay and will only get more popular as more effective and efficient treatments become available.

The pathogenesis of cellulite

The causes of cellulite can be classified as multifactorial. Gender, anatomy, genetic susceptibility, hormones, deficiencies in lymphatic drainage and microvasculature are all thought to play in a role in the condition's pathogenesis (Christman et al, 2017). In 1978, Nurnberger and Muller proposed that the topographic alteration of skin affected by cellulite was secondary to adipose tissue protruding into weakened dermal tissue (Nurnberger and Muller, 1978). Mirrashed et al (2004) confirmed this with an MRI study of posterolateral thigh skin in both females and males. They found a diffuse pattern of extrusion of underlying adipose tissue into the dermis, correlating with cellulite grading (Mirrashed et al, 2004). Further MRI evaluations of cellulite depressions by Hexsel et al (2009) revealed fibrous septa in 96.7% of the depressions; all were found to be orientated perpendicular to the skin surface. These fibrous septa were also significantly thickened compared with septa in skin not affected by cellulite (Hexsel et al, 2009). These findings were further confirmed by a Japanese study that used transmission electron microscopy to examine punch biopsies from skin with cellulite. The microphotography demonstrated the presence of fibrotic septa that acted as a tethering system and producing the typical dimpling pattern found in cellulite (Omi et al, 2013). Additionally, the photos showed proliferation of collagen and elastin fibres into the cellulite tissue, with compression of capillaries and congestion of arterioles, resulting in poor blood flow.

It is widely accepted that the perpendicular orientation of the septa is much more common in women and that, in men, the oblique nature of these fibres appears to prevent underlying fat from protruding (Luebberding et al, 2015). However, the true cause of the thickening and sclerosis of these septa is still debated. Oestrogens and progesterones are often cited as the culprits. These hormones allow for the release of metalloproteases (MMPs), which are required for uterine lining sloughing (menstruation) to occur. These MMPs, including collagenase-1 and gelatinase-1, can also cause dermal collagen breakdown (Draelos, 2005). This may lead to an inflammatory cascade effect, with subsequent changes in microvasculature, increased oedema, lymphatic malfunction and capillary network loss. Ultimately, this may lead to the thickened, sclerotic tethering of the septa and explain the female predominance of cellulite (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Female and male skin

Figure 1. Female and male skin

As there is still debate on the true aetiology of cellulite, it is not surprising that effective treatments have remained elusive. Avram's 2004 review concluded that ‘there are no truly effective treatments for cellulite’, and, over 10 years later, Luebberding et al (2015) concluded much the same. They evaluated 67 papers on various cellulite treatments and determined that ‘no clear evidence of good efficacy could be identified in any of the evaluated cellulite treatments’ (Luebberding et al, 2015). Additionally, Zerini et al (2015) evaluated 73 papers on cellulite treatments and summarised that ‘it is still difficult to indicate an exclusive and effective treatment for this condition’.

However, clinicians now have a better understanding of the structural changes that occur in cellulite and can direct treatments to modify these changes. Bass and Kaminer (2020) reported that ‘clinical studies targeting the collagen-rich fibrous septa in cellulite dimples through mechanical, surgical or enzymatic approaches suggest that targeting fibrous septa is the strategy most likely to provide durable improvement in skin topography and the appearance of cellulite’ (Bass and Kaminer, 2020). Strategies such as severing the septa by subcision, lasers or collagenase, which release the tethering effect of the sclerosed septa, can help smooth the skin's surface. Combined with treatments to strengthen and firm the dermis, such as dermal fillers, radiofrequency and collagen induction therapy, the appearance of cellulite can be improved. However, preventing or completely eliminating cellulite is still unachievable.

Treatment options

A plethora of remedies are available to treat cellulite; many provide temporary improvement, while some have no effect at all. Many of these treatments may best be reserved for maintenance therapy after actual destruction of the fibrous septa, as previously described. Products such as topical creams that contain retinoids and methylxanthines may play a role by stimulating microcirculation, promoting lipolysis and increasing dermal neocollagenesis (Friedmann et al, 2017).

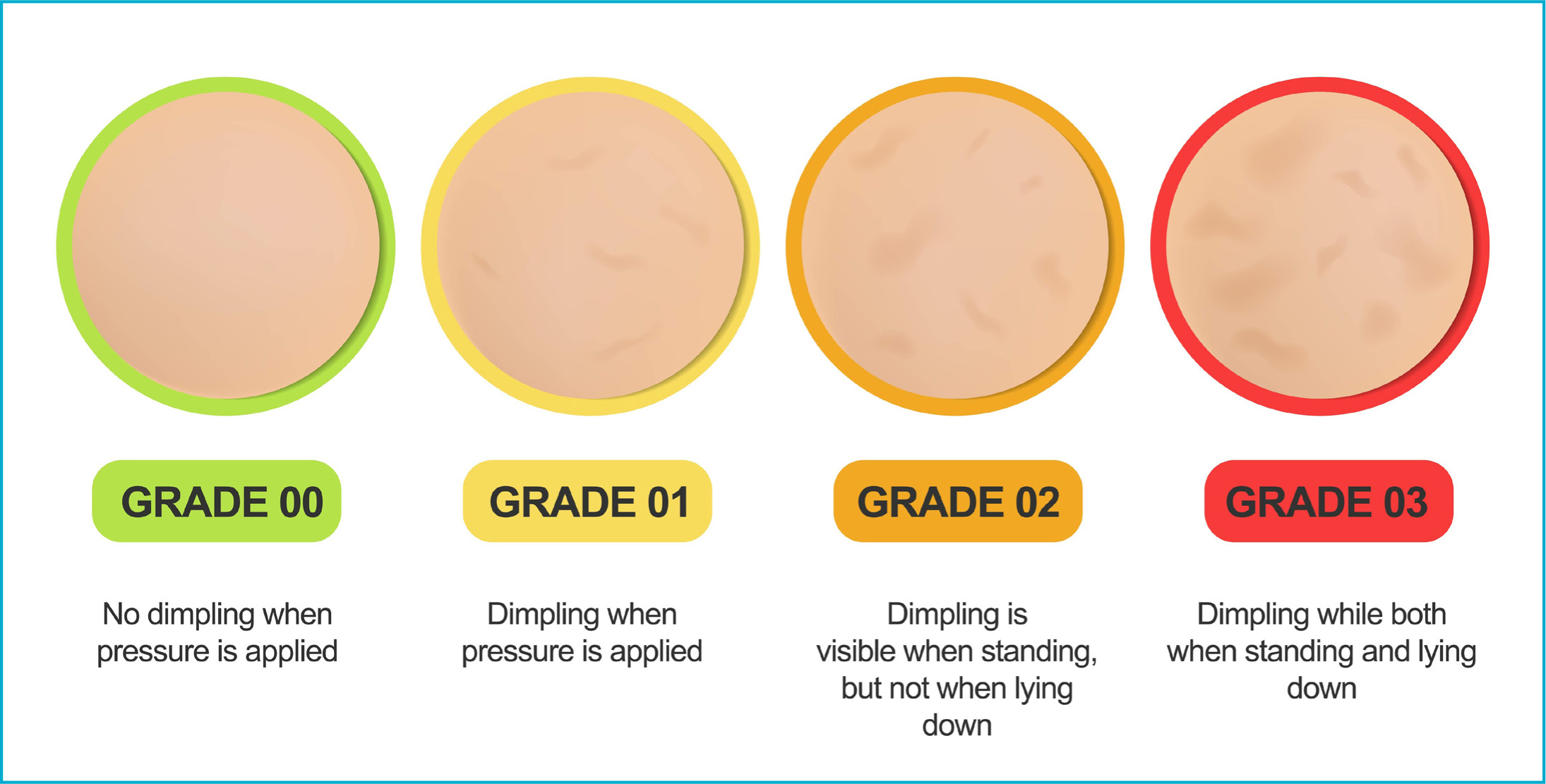

Endermologie, developed in the 1970s and still in use today, involves manipulating the skin and subcutaneous tissue between two revolving rollers (Christman et al, 2017). This device was found to improve the appearance of cellulite in only 15% of patients, although all patients experienced a reduction in body circumference (Gulec, 2009). Acoustic wave therapy, including extracorporeal shockwave therapy (ESWT) and radial shockwave therapy (RSWT), can improve cellulite grade by at least one (Figure 2) (Schlaudraff et al, 2014), but long-term studies on the results are lacking. Radiofrequency and high-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) devices can be helpful, but they seem to be most efficient at reducing subcutaneous fat and decreasing body circumference, rather than directly smoothing cellulite (Alizadeh et al, 2016). In a review of radiofrequency, HIFU, cryolipolysis and ESWT for body contouring and the treatment of cellulite, Alizadeh et al (2016) concluded that there was no one definitive treatment for cellulite. Again, these devices may be best employed for maintenance therapy or in combination with septa lysis.

Figure 2. Cellulite grade

Figure 2. Cellulite grade

Subcision

Subcision is a technique used to sever and release the fibrous septa responsible for dimpling and skin depressions in cellulite. It was originally a technique to treat depressed acne scars and small areas of skin dimpling. A needle, blade or ‘duck beak’ cannula with a sharp edge is inserted into the skin and feathered or swept back and forth in the subdermal plain, parallel to the skin surface (Uebel et al, 2018). The clinical improvement seen after severing the fibrous septations is likely, in part, due to the redistribution of subcutaneous tension forces, mitigating fat protrusion and reallocation of fat lobules into spaces created by the procedure (Friedmann et al, 2017). Many patients have pain, bruising and haemosiderosis following the procedure, but report a high degree of satisfaction (Hexsel and Mazzuco, 2001).

A vacuum-assisted subcision or tissue stabilised–guided subcision (TS-GS) device was introduced to the market in 2017. It consists of a vacuum chamber that lifts and stabilises the target area, before infiltrating a tumescent anaesthesia and inserting a motorised microblade to perform subcision (Brauer et al, 2018). In a review of 25 patients who had a single treatment of TS-GS, known as Cellfina, patient satisfaction was found to be high at 95.6%; however, these results were obtained only at 3 months post-treatment (Nikolis et al, 2019). Longevity of the results was evaluated by Kaminer et al (2017), who treated 45 patients with a single Cellfina treatment and followed them up for 3 years. Patient satisfaction was reported to be high after 1 year and remained that way, with 94% of patients still satisfied after 3 years (Kaminer et al, 2017).

Laser subcision

Laser subcision, instead of mechanical subcision, is another, albeit more expensive, option for treating cellulite. The advantage of laser usage is the additional possible thermal destruction of protruding adipocytes and thermal stimulation of dermal collagen. A 1440 nm ND:Yag laser with a side-firing fibre and attached temperature-sensing cannula, named Cellulaze, was brought to market in 2012. Its side-firing fibre can be inserted in the hypodermis and placed in different positions to target fat cells, septa and the dermal–hypodermis interface. In a 2013 study, which was paid for by the company, single Cellulaze treatment outcomes ‘support the results of previous studies demonstrating significant efficacy at a 6-month period utilising both subjective and quantitative measurements’ (Katz, 2013). A German report came to similar conclusions, stating that, at 6 months, the 1440 nm laser improved the appearance of cellulite and yielded 100% satisfaction (Hoffman, 2017). A further study by DiBernardo et al (2016) demonstrated safety and maintained effectiveness of one Cellulaze treatment at 1-year post treatment, and a study by Sasaki (2013) demonstrated the same thing at 2 years.

Enzymatic subcision

Enzymatic subcision of the septa in cellulite is the newest addition to the cellulite treatment armamentarium. Collagenase clostridium histolyticum (CCH) was first isolated in the 1950s. It is a combination of two bacterial collagenases (AUX-I and AUX-II) in an approximate 1:1 ratio, which are isolated and purified from the fermentation of Clostridium histolyticum bacteria. It hydrolyses collagen in its native triple helix form under physiological conditions (Qwo, 2020). CCH was US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved in the US in 2010 for the treatment of Dupuytren's contracture, and then in 2013 for Peyronie's disease (Drugs.com, 2021). In 2020, the FDA approved the use of CCH in the US for treatment of moderate-to-severe cellulite in the buttocks of adult women. CCH has been used off-label to successfully treat the fibrous capsules of lipomas via injection (Boyer et al, 2015). Injectable CCH has also been used to treat keloids and uterine fibroids, while topical CCH ointment is used to treat diabetic foot ulcers and debride burn wounds (Alipour et al, 2016). CCH is a useful and versatile tool.

An early study for the use of CCH in treating cellulite looked at 375 women who were injected in three treatment sessions, which were separated by approximately 21 days, versus placebo. Injections were performed with the patient prone, into predetermined dimples that were identified while the patient was standing. Significant improvement was reported by both the clinicians and patients (Sadick et al, 2019). Further reports by Kaufman-Janette et al (2020) found improvement in both clinical and patient ratings in over 75% of the women treated, and the results were durable up to the 2-year follow-up. Kaufman-Janette (2021) also performed a placebo-controlled, double-blind study on 843 women treated with CCH, which is the largest study to date. Results were consistent, with the majority seeing improvement of one point or more on a six-point scale. Significant bruising was a prominent side effect that was reported in all the studies. No quantifiable circulating CCH was observed in healthy women after a single subcutaneous dose up to 3.36 mg (Bhatia et al, 2020), with 0.84 mg being the recommended dose per treatment area. Interestingly, all of these studies noted that many of the women developed antibodies against AUX-I and AUX-II, but no hypersensitivity reactions were observed (Sadick et al, 2019). The clinical significance of this finding is unclear, but the presence of neutralising antibodies does not affect clinical response or the frequency of adverse events (Bhatia et al, 2020). Figures 3 and 4 demonstrate patients who were treated only with CCH, called ‘Qwo’ in the US.

Figure 3. Before (top) and after (bottom) three treatments of collagenase clostridium histolyticum

Figure 3. Before (top) and after (bottom) three treatments of collagenase clostridium histolyticum  Figure 4. Before (top) and after (bottom) two collagenase clostridium histolyticum treatments (three treatments are recommended by the manufacturer)

Figure 4. Before (top) and after (bottom) two collagenase clostridium histolyticum treatments (three treatments are recommended by the manufacturer)

» Treatments to sever the septa, strengthen the dermis and, occasionally, to eliminate selective adipose tissue, will yield better results when combined, rather than any one individual treatment on its own «

Combination treatments

It is difficult to treat cellulite without some sort of disruption of the fibrous septa. However, it is important to remember that skin laxity and weakness are contributing factors to the severity of the cellulite. A decrease in containment forces occurs with increasing age as the skin thins by 0.3% per year (Rudolph et al, 2019), and the superficial fascial system becomes less stable. Treatments meant to thicken the dermis and provide stability to the skin structure can help ‘tack down’ adipose cells and smooth the surface. In 2019, Davis et al published a review of combination treatments, including topical agents, controlled subcision, energy-based devices (for example, radiofrequency and microfocused ultrasound), biostimulatory dermal filers and CCH, meant to treat both the dermis and the septa. Some of the popular combinations reported in the literature include subcision with either dilute calcium hydroxyapatite injections or poly-L-lactic acid injections and/or microfocused ultrasound (Casabona and Pereira, 2017; Mazzuco, 2020; Swearington et al, 2021). In short, as the causes of cellulite are multifactorial, treatments should be too. Treatments to sever the septa, strengthen the dermis and, occasionally, to eliminate selective adipose tissue, will yield better results when combined, rather than any one individual treatment on its own.

Conclusion

It is unlikely that there will be a ‘cure’ for cellulite in the near future, and whether it even needs to be ‘cured’ is up for debate. Regardless of how socially acceptable cellulite becomes, in the author's opinion, many women may continue to dislike it and seek treatments to try to improve it. Cellulite is thought to be caused by multiple factors, most prominently, hormonal influence on dermal collagen modelling and remodelling, but also genetic disposition, microcirculation malfunctions and anatomical factors. Hormonal and inflammatory effects cause fibrosis and sclerosis of the septa in the subcutaneous tissue. This tethers the skin down and allows fat to protrude, causing the classic dimpling on the skin the surface. Procedures aimed at severing these septa need to be included in any cellulite treatment regimen, and these are best combined with treatments that strengthen the dermis and help eliminate protruding adiposity. Long-term results will most likely require some kind of maintenance therapy. The best protocols and treatment combinations are still to be determined.

Key points

- Cellulite is a result of dermal laxity combined with the formation of fibrous dermal septae, causing a change in the surface skin topography

- There is no definitive cure for cellulite

- Treatment options include subcision of the dermal septae mechanically, enzymatically or via laser energy

- Subcision, combined with dermal strengthening options, such as laser treatments or dilute filler, is most likely to achieve the best result.

CPD reflective questions

- What is the aetiology of cellulite, and why is it so hard to treat?

- Are societal norms shifting towards more acceptance of cellulite and, if so, will patients continue to seek treatment for it?

- What treatments improve the appearance of cellulite the most and why?